What are primary/secondary academic sources?

This is the third and final chapter about Finding Academic Sources. To complete this reader, read each chapter carefully and then unlock and complete our materials to check your understanding.

– Explore the differences between primary and secondary sources

– Provide examples of primary and secondary sources for comparison

– Highlight why such distinctions exist in academic research

Before you begin reading...

-

video and audio texts

-

knowledge checks and quizzes

-

skills practices, tasks and assignments

Chapter 3

For information and practise about finding academic sources that goes beyond this short reader, you may also wish to take our readers on conducting digital searches and identifying source value. Don’t forget also that for only a few Academic Marks you can test your understanding of these topics by accessing and completing our beginner-, intermediate- and advanced-level worksheets.

This third and final chapter about finding academic sources focusses on the topic of identifying the similarities and differences between primary and secondary sources. Because there are significant differences in how primary and secondary sources are viewed by academics and tutors (and how they’re cited within a text), it’s important for students to not only recognise a primary source when they see one, but to also understand why such source differentiation exists.

What is a primary source?

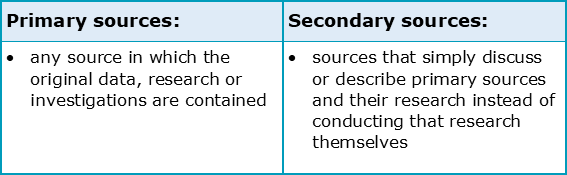

We’ve already discussed how a source is generally “any complete text, whether written, spoken or captured in image form, that may be used to provide evidence, examples or background information for a piece of research”, but what we haven’t yet explained is how sources may be divided into primary and secondary categories, and why such a distinction exists in academia. Generally, a primary source is any source in which the original data, research or investigations are described and contained. A journal article, for example, that explains the research its author(s) have conducted would be considered a primary source, just as handwritten diary entries or authentic recordings would be primary sources because they contain the original works of their authors.

Some subjects such as history or international studies demand the investigation and use of primary sources more than other subjects do. When studying history, for example, it’s particularly important for the researcher to find and read the most original source possible, which may be in the form of photos, posters, diaries or ancient and authentic scripts and texts. When studying economics on the other hand, it may instead be adequate to simply use secondary sources that describe others’ research as the main evidence of your investigation.

What is a secondary source?

While primary sources either document the research their authors have personally conducted or are the product of the primary author’s creative expression (such as recordings or diary entries), secondary sources are those documents that simply discuss or describe primary sources and their research instead of conducting that research themselves. In other words, secondary sources use, discuss and critique primary sources in order to create their content, perhaps investigating multiple primary sources as a literary review or to initiate debate with the original authors. Source types that may be commonly considered as secondary are therefore textbooks, journal articles and websites.

Can a source be both primary and secondary?

Adding some confusion to the matter is that under the right circumstances a source may be both primary and secondary. Journal articles which have conducted their own research, for example, will also usually refer to the research of others in their literature review. When discussing its own research, such a journal article may therefore be considered as being primary, but when discussing the research of other sources and other authors, this same source would then become secondary as it is now merely interpreting the research of another publication. Ultimately, although this added complication holds little relevance to how such sources are used by the researcher, this distinction further completes a student’s understanding of what it means for a source to be either primary or secondary.

Why are these distinctions important?

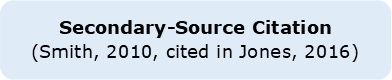

Finally, why is it important to recognise the differences between primary/secondary sources in academia, and how does doing so assist a researcher when finding academic sources? The first reason in answer to this question is practical, and has to do with referencing practices. As can be seen in the following in-text citations, when a researcher wishes to cite a primary source that they’ve only read about in a secondary source, there is a significant difference in how such citations are created:

The above normal citation indicates that the researcher has personally read the original research conducted by Smith (2010), whereas the example secondary-source citation instead indicates that the researcher has only read about Smith’s (2010) research in a secondary source: Jones (2016). Because a researcher should include in their reference list only those sources they’ve directly read, if Smith (2010) was explained in Jones (2016) but wasn’t read directly, then only the secondary source Jones (2016) should be added to that researcher’s reference list and not the primary source Smith (2010).

Another reason for distinguishing primary from secondary sources when researching is related to maintaining quality investigations. Let’s take, for example, our previous secondary-source citation and say that a researcher named Mark had only read about Smith (2010) in Jones (2016). What this means is that Mark’s understanding of Smith’s (2010) publication will not only include Mark’s interpretation of that research, but it will also include Jones’s (2016) interpretation of Smith (2010) as well as Mark’s interpretation of Jones’s interpretation! As you can see then, reading the primary source wherever possible is often recommended by universities to avoid such potential for misinterpretation, particularly towards the end of a bachelor’s degree and beyond when research becomes more vigorous. Ultimately, when an academic is attempting to find appropriate sources, that academic should try their best to locate and include the primary sources that have conducted the research themselves or that constitute the original creative expression.

Downloadables

Once you’ve completed all three chapters about finding academic sources, you might also wish to download our beginner, intermediate and advanced worksheets to test your progress or print for your students. These professional PDF worksheets can be easily accessed for only a few Academic Marks.

Collect Academic Marks

-

100 Marks for joining

-

25 Marks for daily e-learning

-

100-200 for feedback/testimonials

-

100-500 for referring your colleages/friends