What are the thirteen types of English verb?

This is the third of five chapters About Verbs. To complete this reader, read each chapter carefully and then unlock and complete our materials to check your understanding.

– Discuss the concept of dividing verbs into various types

– Introduce thirteen types of verb in the English language

– Provide expressions and examples of each type to help guide the reader toward accurate identification

Before you begin reading...

-

video and audio texts

-

knowledge checks and quizzes

-

skills practices, tasks and assignments

Chapter 3

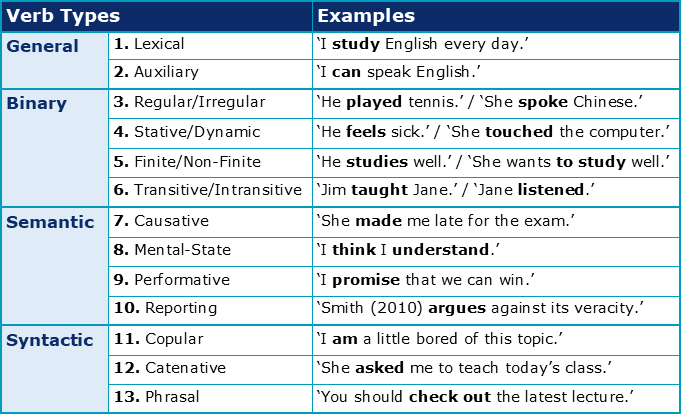

Now that Chapters 1 and 2 are completed, you should hopefully feel more confident about identifying English verbs and understanding their various functions. This third chapter on the subject next aims to explore and exemplify the thirteen different categories of verb that may be encountered either in every day speech or in academic writing. The following table briefly outlines these thirteen verb types, each of which will be discussed in turn and in detail. Please note that (a) these categories have been subdivided into general, binary, semantic (meaning-based) and syntactic (structure-based) categories, and (b) some verbs may be acceptable in more than one category:

General Categories

Both lexical and auxiliary verbs are considered to be general verb types as these are the broadest of verb classifications. In truth, every one of the remaining eleven types explored in this chapter could also be considered as being either lexical or auxiliary in nature, making these two classifications primary and most important.

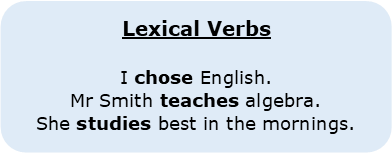

Type 1: Lexical Verbs

Also known as ‘main’ verbs, lexical verbs are the most common verb type in the English language. Lexical verbs express a clear meaning and do not rely on any other verb to be grammatical, although they can be used in conjunction with other verbs to create larger verb phrases in a clause. Because by definition these verbs carry significant meaning, many other types in this list are also lexical in nature.

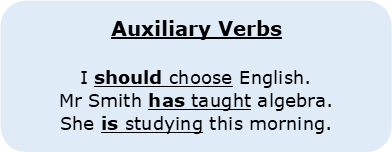

Type 2: Auxiliary Verbs

Unlike lexical verbs, auxiliary verbs do not contain much of the meaning of an expression and are instead used to show grammatical features, such as tense, aspect or modality. Also known as ‘helping’ verbs, auxiliaries are most usually placed directly before lexical verbs within a sentence. As is visible in the following examples, auxiliary verbs such as ‘should’, ‘have’ and ‘be’ may be used to show obligatory modality, the perfect aspect and the continuous aspect, respectively:

Auxiliary verbs can be easily recognised by their two unique features, which are (1) they require subject-auxiliary inversion when forming questions (such as where ‘should’ comes before the subject ‘I’ in ‘should I choose English?’), and (2) they are followed by the negator ‘not’ in negative constructions (as in ‘you should not choose English’). Because of additional unique auxiliary features, this verb type can also be further categorised in two ways: primary and modal auxiliaries.

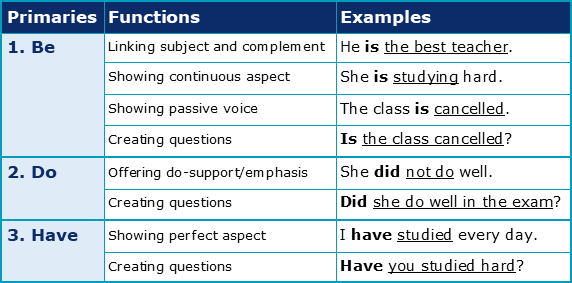

2.1 Primary Auxiliary Verbs

There are three primary auxiliary verbs in the English language, and each has their own forms and functions. These three verbs are ‘be’, ‘do’ and ‘have’:

2.2 Modal Auxiliary Verbs

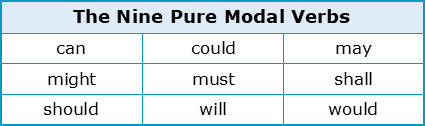

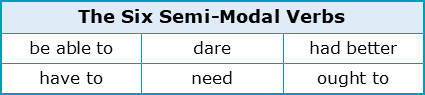

In addition to these three primary auxiliary verbs, there are nine pure modal and six semi-modal auxiliary verbs that academic students should learn to use and recognise, particularly when expressing modality in speech or when writing assignments. Modality is a very helpful linguistic feature that communicates a speaker’s attitudes about the world around them, either through judgements, assessments or interpretations of the believability, reality, obligation or desirability of a proposition. Due to its usefulness, students may therefore wish to take our short reader about the grammar of the following fifteen modal verbs:

Binary Categories

The next four classifications of verb are grouped together because they exist in an either/or scenario, in which these words either are or are not semantically, morphologically or syntactically regular, stative, finite or transitive.

Type 3: Regular/Irregular Verbs

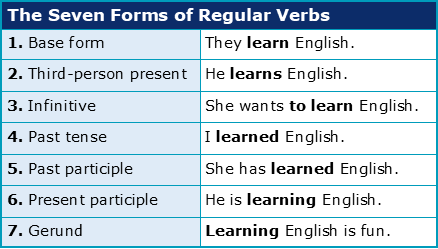

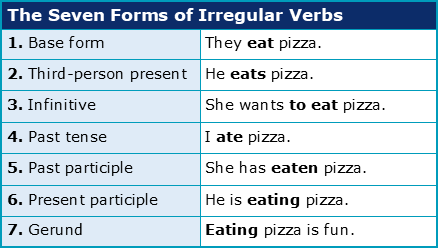

One of the most common binary distinctions among verbs is whether or not they’re regular in how they’re morphologically formed. Thinking back to Chapter 2 when the seven verb forms were introduced (such as the base form or past participle), an irregular verb is one whose seven formations cannot be easily predicted. While at one end of the regularity spectrum are some highly irregular verbs such as ‘be’, and at the other end the relatively formless modals ‘can’ or ‘should’, most verbs fall into the regular category. Generally speaking, regular verbs have one principal part called the base form from which all other forms are predictably created.

Looking at the example regular verb ‘learn’ in the following table, it’s clear to see that the third-person present form ‘learns’ is created using the suffix ‘-s’ and the past tense and participle forms ‘learned’ are made by adding ‘-ed’:

Irregular verbs on the other hand such as ‘eat’ are said to have three principal parts since their past tense (‘ate’) and past participle (‘eaten’) forms are more difficult to predict. While there may be some discernible patterns among irregular verbs, these verbs are still irregular in that they do not follow common structures:

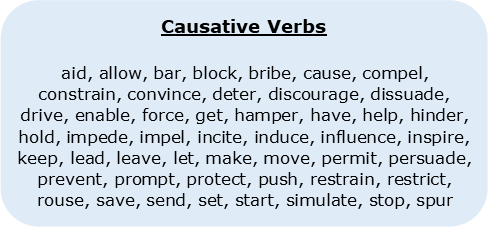

Type 4: Stative/Dynamic Verbs

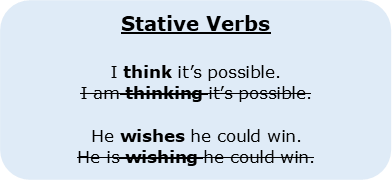

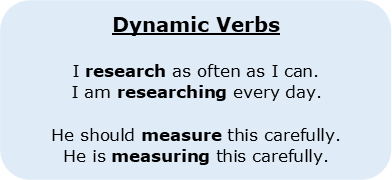

Another common way of categorising verbs is by dividing them into stative and dynamic types depending upon the action, event, occurrence or state of being they describe. Stative verbs are generally those verbs such as ‘think’ or ‘wish’ which describe conditions or states of being that are undefinable in duration or are unchanging. Dynamic verbs, on the other hand, such as ‘research’ or ‘measure’, describe actions and events that most commonly have a beginning and an end.

As is demonstrated in the following examples, the importance of this stative/dynamic distinction becomes clearer when we see that it’s ungrammatical to use the continuous ‘-ing’ aspect with stative verbs:

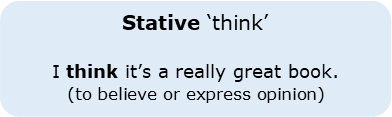

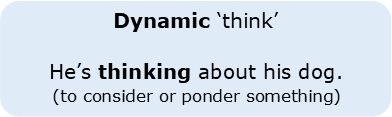

Please note, however, that some verbs may be both dynamic and stative depending upon their meaning, such as the verb ‘think’ in the following expressions:

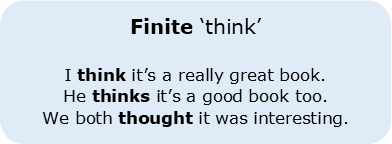

Type 5: Finite/Non-Finite Verbs

Another binary classification that academic students may come across when identifying verbs describes whether or not a verb is finite, which is the ability to express tense or agreement with a related subject. While finite verbs can demonstrate tense and subject-verb agreement, and can occur as the singular verb of an independent clause, non-finite verbs cannot show such grammatical flexibility. As the following examples demonstrate, non-finite verbs cannot be inflected and can only occur alone in a clause when that clause is dependent:

When remembering the seven verb forms that we introduced in Chapter 2, it becomes clear that non-finite verbs are usually infinitives, participles and gerunds.

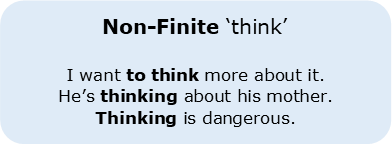

Type 6: Transitive/Intransitive Verbs

The final binary distinction among verbs explores whether or not a verb is transitive and can take an object or intransitive and cannot. Two things can be noticed in the following table: (1) transitive verbs have three types depending on how many arguments (subjects and objects) they can take, and (2) verbs such as ‘melt’ may be both intransitive and transitive depending on their use and meaning:

Semantic Categories

Another method for categorising verbs is by grouping them semantically – based on their meanings. Four different such types have been identified below.

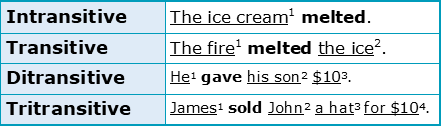

Type 7: Causative Verbs

The first semantic category of verbs are called causatives. Causative verbs such as ‘let’, ‘have’ and ‘make’ express the act of one person or thing causing another person or thing to do or receive something, as in the expression ‘you should let him help you study’. There are roughly fifty verbs in the English language that are able to form transitivity-increasing causative constructions:

Type 8: Mental-State Verbs

Related to deciding, discovering, planning, understanding, and the general contents of our minds that cannot be externally evaluated, mental-state verbs such as ‘know’, ‘hope’ or ‘believe’ are most often stative and extremely polysemous – indicating that each verb can demonstrate a variety of state-based meanings. In academic argumentative writing, such verbs can be particularly useful when qualifying the opinions and facts of other authors. Indeed, it’s far more common and cautious to use expressions such as ‘researchers believe that…’ than overly confident expressions such as ‘it is a fact that…’.

Type 9: Performative Verbs

The third semantic categorisation describes those limited set of verbs that clearly demonstrate a speech-act being performed. In other words, the word being said creates the action being described, such as ‘promise’ in ‘I promise to be on time’ or ‘apologise’ in ‘I apologise for being late’. In both these examples, the performative verbs ‘promise’ and ‘apologise’ create the very assurance and the apology.

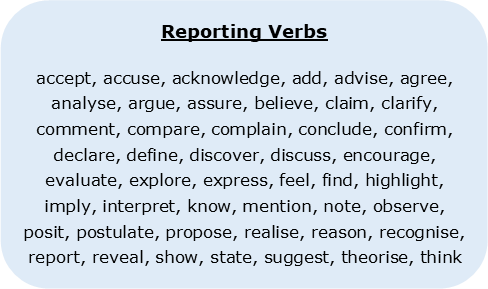

Type 10: Reporting Verbs

The final semantic category of verb is the reporting verb, which is a verb type that allows the speaker or writer to directly or indirectly report the words of others. Such verbs as ‘argue’ or ‘note’ are particularly useful in academic writing as they allow the writer to introduce sources into their research through expressions such as ‘Smith (2010) argues that 90% of air pollution is created in Asia’:

Syntactic Categories

The final three verb types have been categorised mostly by the syntactic structures they require, such as whether a particular verb must be followed by a complement, a verb phrase or a specific particle, preposition or adverb.

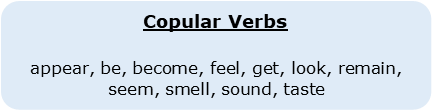

Type 11: Copular Verbs

Copular (or linking) verbs are a restricted set of verbs such as ‘be’ or ‘feel’ that may not take objects within a clause. Instead, to be grammatical, copular verbs require a nominal or adjectival complement that provides more information about the clause subject, such as ‘Mr Smith is a teacher’ or ‘Jane feels sick’. In both of these examples, the complements ‘a teacher’ and ‘sick’ provide more information about the subjects ‘Mr Smith’ and ‘Jane’, respectively. Because the copular verbs ‘be’ and ‘feel’ in these examples could be replaced with an equals sign (=) and the meaning would be much the same, this demonstrates that copular verbs carry little meaning and are more grammatical in nature – connecting subject with complement:

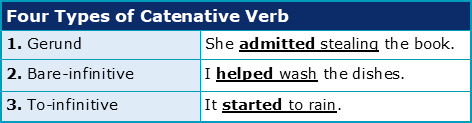

Type 12: Catenative Verbs

Catenative verbs are those special types of lexical verbs such as ‘want’, ‘like’ or ‘help’ that aren’t primary or modal auxiliary verbs but that can be followed by another lexical verb within the same clause. Derived from the Latin word for ‘chain’, catenative verbs are special in that they may be used in combination to create a chain of non-finite verbal complements, as in the following example: ‘We agreed to try to buy a new laptop today’. The type of non-finite verb that’s required in such a chain however (whether a gerund, a bare-infinitive or a to-infinitive), depends entirely on the verb – with some verbs being able to take multiple types:

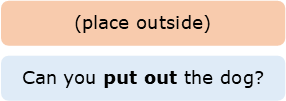

Type 13: Phrasal Verbs

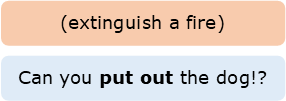

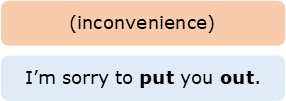

The final verb type on our list is the phrasal verb, which is one of the most common and challenging verb types for non-native speakers of English. In brief, a phrasal verb is a combination of a lexical verb and either a preposition or an adverbial particle (or both) that creates a unique and often idiomatic meaning:

Because such verbs are so varied and complex in their grammar, you may wish to complete our short reader specifically on the subject of phrasal verbs.

Downloables

Once you’ve completed all five chapters about verbs, you might also wish to download our beginner, intermediate and advanced worksheets to test your progress or print for your students. These professional PDF worksheets can be easily accessed for only a few Academic Marks.

Collect Academic Marks

-

100 Marks for joining

-

25 Marks for daily e-learning

-

100-200 for feedback/testimonials

-

100-500 for referring your colleages/friends